Building Dialogs

Start: October 08, 2020

AMA Art Museum of the Americas

201 18th Street, NW

Washington, DC 20006

United States of America

Phone: +1 202-370-0149

E-mail: aospinaj@oas.org

www.museum.oas.org

Art Museum of the Americas

F Street Gallery

Building Dialogs

On March 13, 2020, along with all other museums, galleries, and other cultural institutions, the AMA implemented a sudden shift away from our physical space into an entirely online space -#AMAatHome / #AMAenCasa. Once an augmentation of our in-person exhibitions and events, our four social media walls transformed overnight into our default spaces for programming, due to Covid-19-related public health regulations.

For the Building Dialogs project, Fabian Goncalves initiates a process in which a group of artists select their own pairings of each other's works, creating their own multi-layered narratives. Stimulating the conversation among this small network of artists, we pivot from a vertical to horizontal curatorial practice, we reinforce lateral contributions and visual syntheses, and we question the monolithic idea of authorship. Each pairing contributes to a transformative dialog, synthesized through the eyes of the beholder. In conversation with Gesche Würfel, they construct this conceptual base for transformative visual dialogs among the four selected photo artists: Alejandra Delgado Uria, Thomas Kellner, Brad Temkin, and Gesche Würfel.

The four photographers allowed for their images to be paired with those of the other artists, creating diptychs, inevitably affecting changes in perception. The artists also agreed to house their own versions of Building Dialogs on their websites and link them to #AMAatHome and the other artists’ renderings. Gesche drafted the first visual dialog, as a spark for the other three artists to create their own collaborative Building Dialogs: Gesche Würfel, Alejandra Delgado Uria, Thomas Kellner, and Brad Temkin.

The AMA F Street Gallery #AMAatHome / #AMAenCasa aims to share this experience with major photography festivals, such as FotoFest, Houston, USA; Festival de la Luz, Buenos Aires, Argentina; Fest-Photo, Puerto Alleger, Brazil; Luz del Norte, Monterrey, México and Photo Lima, Lima, Peru.

We embrace the heightened significance of our online platforms, and while we cannot expect for virtual walls to be interchangeable with physical walls, they may indeed harbor potential for revitalized cultural exchange.

Curators

Fabian Goncalves Borrega

Exhibitions Coordinator

Art Museum of the Americas, Washington DC, USA

Dedicated to the arts of the Americas, the Museum preserves, studies, and exhibits works by outstanding artists and carries out other activities of an educational nature to increase understanding and appreciation of the cultures of the Americas. The museum's permanent collection of 20th-century Latin American and Caribbean art is one of the most important collections of its kind in the United States. Equally important is it growing collection of contemporary photography.

Gesche Würfel is a Teaching Assistant Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (USA). She received an MFA in Studio Art from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (USA), an MA in Photography and Urban Cultures from Goldsmiths, University of London (UK), and a diploma in Spatial Planning from the Technical University Dortmund (Germany). Curatorial projects include among others the Building Conversations exhibition, an annual exhibition series of African student photographers at the Allcott Gallery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (USA), and annual student exhibitions on and off campus.

Alejandra Delgado Uría

Alejandra Delgado Uría (Bolivia) lives and works in Lima, Peru. She graduated from the National Academy of Fine Arts "Hernando Siles" of La Paz Bolivia, in 2001 and Master in Photography at the EFTI Center of Image School of Photography, Madrid, in 2007. She has done artistic residencies at KIOSKO Gallery, Bolivia in 2008 and at the Can Xalant Center, Barcelona Spain in 2010. Her work is carried out both in the two-dimensional media of photography and in installations, performance and video art. She has presented nine individual exhibitions between Peru and Bolivia and has exhibited collectively since 2002 both in Bolivia and abroad.

Thomas Kellner

Thomas Kellner was born in Bonn in 1966. He studied art, sociology, politics and economics at the University of Siegen. In 1996 he received the Kodak Young Talent Award, which encouraged him to live as an artist. Since then, Kellner has been living in Siegen as an artist and curator of photographic exhibition projects. In 2003 he was appointed to the German Society for Photography (DGPh). Thomas Kellner has shown his work in solo exhibitions in Germany, Australia, Russia, China, France, Poland, Denmark, Brazil and the USA since 2002 and has been involved in numerous group exhibitions and publications. His works are represented in important private and public collections.

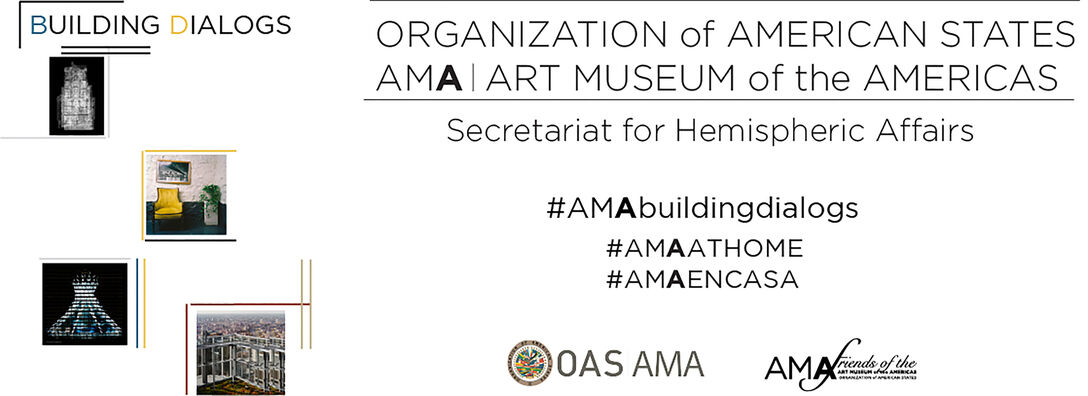

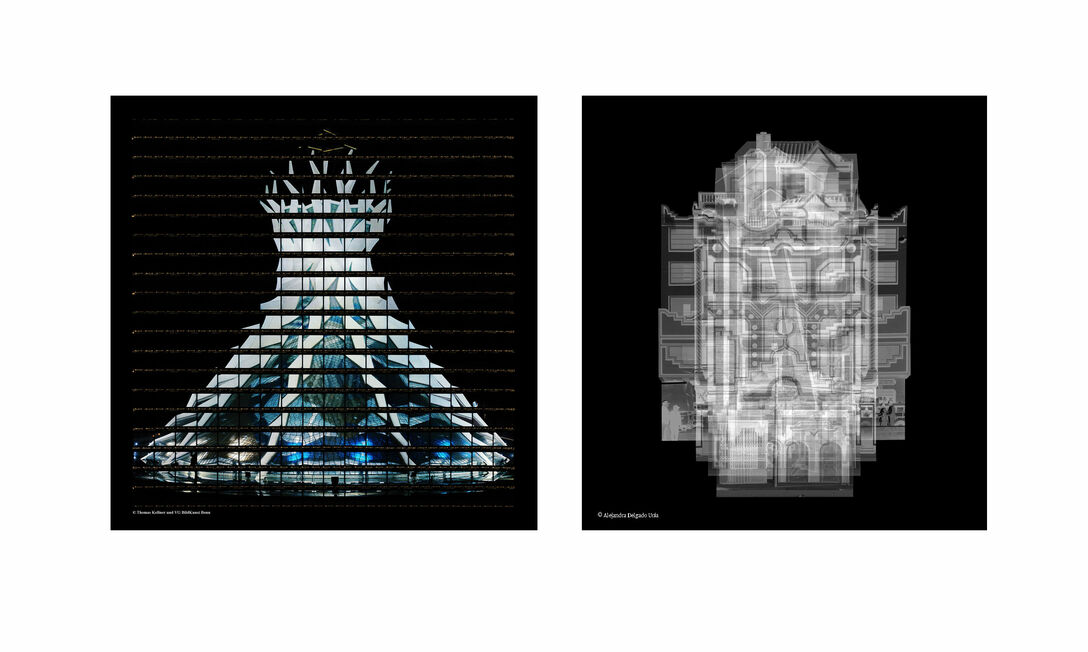

Thomas Kellner is known for his photographs of seemingly dancing architectural attractions from all over the world. Prof. Dr. Irina Chmyreva has described his work as unique "Visual Analytical Synthesis". In which he does not only one shot, but many planned ones are shot in series in order to merge them into contact sheets.

Thomas Kellner’s works imitate the wandering look of the eye, showing us segments of the total, which come together as one image. His photographs reconstruct our view on architecture or the object.

Brad Temkin

Brad Temkin (American, b.1956) is perhaps best known for his photographs of contemporary landscape. His work is held in numerous permanent collections, including those of The Art Institute of Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Akron Art Museum, Ohio; Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Ft Worth; and Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, among others. His images have appeared in such publications as Aperture, Black & White Magazine, TIME Magazine and European Photography. He has been awarded numerous grants and fellowships including an Illinois Arts Council Fellowship in 2007 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2017. A monograph of Temkin’s work titled Private Places: Photographs of Chicago Gardens (Center for American Places) was published in 2005. Temkin’s second book titled ROOFTOP (Radius Books) was released Fall 2015, and most recently his third book, The State of Water (Radius Books) released in 2019. He has been an adjunct professor at Columbia College in Chicago since 1984.

Gesche Würfel

Gesche Würfel is a visual artist based in Chapel Hill, NC (USA). Her work has been exhibited, published, and awarded internationally; exhibition venues include the Tate Modern (UK); Blue Sky Gallery, Portland (OR); Center for Photography at Woodstock, NY (USA); Contemporary Art Museum (CAM) Raleigh, NC (USA). Wuerfel is the author of Basement Sanctuaries (Schilt Publishing 2014). Her work has been published in The New York Times, The Guardian, WIRED, and many other outlets. She is a recipient of grants from the Puffin Foundation, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council among others. Wuerfel was named as the Juror’s Pick for the LensCulture Emerging Talent Awards 2016, is a finalist in the 2019, 2018, and 2017 Lange-Taylor Award, and a Top 50 Critical Mass 2017 winner. Collecting institutions are the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Museum, MA (USA) and the Portland Museum of Art, OR (USA). Wuerfel is represented by Tracey Morgan Gallery.

Dialog, a bridge to the unknown

In Inca mythology, the universe was divided into three territories or Pachas: Hanan Pacha, Kay Pacha and Uku Pacha. These realms shared a structure similar to that of the Catholic notions of heaven, earth and hell, which helped Spanish missionaries advance their own religious notions in the New World while simultaneously allowing the Inca to preserve aspects of their own mythology within that of Catholicism, giving rise to syncretic beliefs that remain part of Andean myth and religion to this day.

The three pachas represented three distinct planes of existence, interconnected and bridged by both physical and spiritual and mythological elements. Together, the three realms shaped Inca religion, the concept of the Inca cosmos and the day-to-day worldview of both the Inca nobility and the common man.

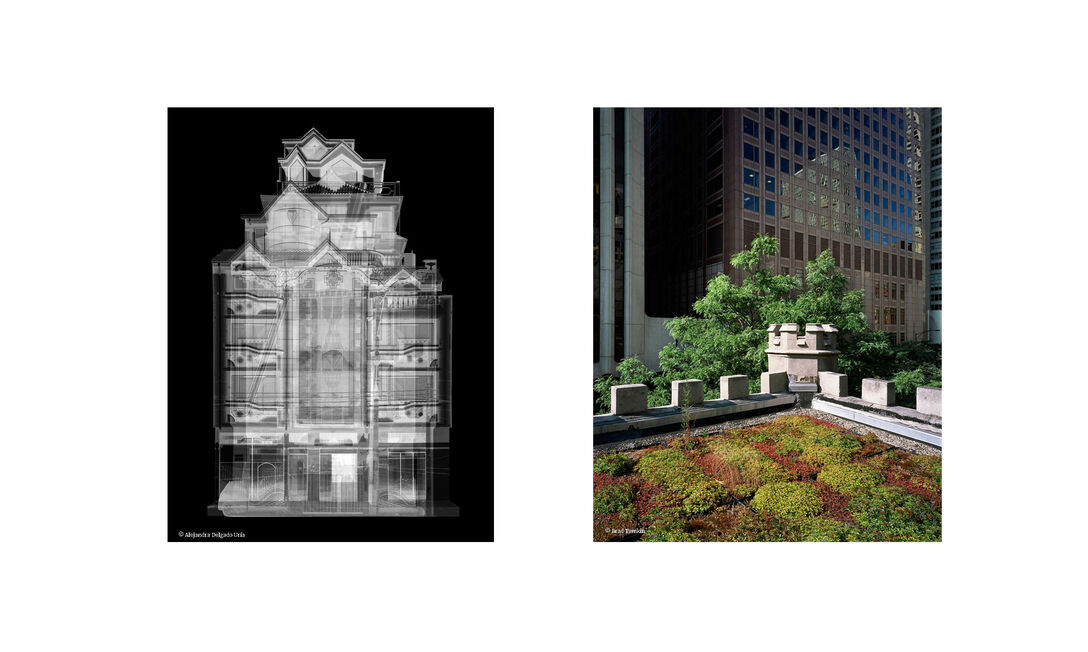

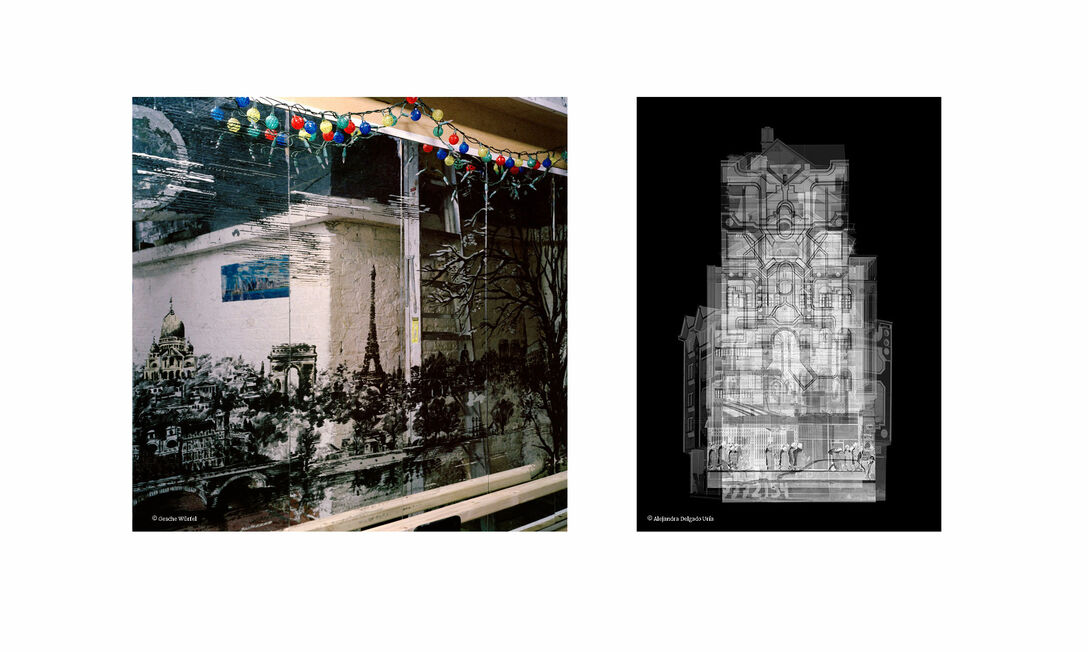

The three Pacha Realms of Inca mythology also shared a structure with buildings’ concepts of rooftops, stories and basements, having a metaphoric and symbolic correlation. Through the vantage point of the photography of four artist who explore these buildings’ main parts, the Hanan Pacha realm is symbolized by Brad Temkin’s Rooftops, a series of ambiguous and solitary gardens against the open Chicago sky. The Kay Pacha realm, representing the building’s central part, is portrayed by Thomas Kellner’s series Brasilia, 50 Years of Utopia, in a melodic deconstruction of facades and interiors of Brasilia, the capital city of Brazil, and by Alejandra Delgado’s series Fantasmagorias, a multi-layer black and white set of images of disembodied architecture of Bolivian Cholets[1].Finally, the Uku Pacha realm is represented by Gesche Würfel’s Basement Sanctuaries, a personalized and intimate view of New York City superintendents’ basements and common areas.

Uku Pacha can be seen as the Inca underworld, beneath the human realm of Kay Pacha, and was, perhaps unsurprisingly, a place where those unfit for Hanan Pacha would go upon their deaths. Uku Pacha can be represented in the European building traditions by basements or cellars originated as storerooms for perishable food, with a design based on farmers’ root-cellars and the expansive undercrofts of palaces and cathedrals, also a place for entombed bodies and detritus from above. Basements are the lowest parts of the building and absorb the earth’s energy of cool darkness, concealment, and insular underworld, and the sacred mystery of the death and rebirth of the deities of vegetation. In contemporary times, they became a place for humble and essential activities: laundry, carpentry, and repairs that support the life in the upper regions[i]. They are the base from where to build, the beginning of a transformative conversation.

Gesche’s Basement Sanctuaries are void, although their presents infer and felt no human presence on her pictures: An allegory of the emptiness left behind by immigrants on their places of origins and their being reborn and/or reemerging in a new place, the Basements Sanctuaries, as superintendents complete the cycle of death and rebirth. These images resembling tunneled catacombs with recycled decorations are reminiscences of the supers’ effort to recreate, based on lingering memories affected by time and trans-acculturalization of places from their past, places that may not even exist anymore. Through captures of colors and forms, Gesche evokes the presence of supers’ families inducing us the viewers to communicate with them[ii].

The Kay Pacha or middle world for the Inca mythology is the physical realm of living beings and the world of birth, death and decay, equivalent to our own inhabited world. The earthly world of Kay Pacha was envisaged as a horizontal area lying between the upper realm of Hanan Pacha and the realm of Uku Pacha below. According to Laura Laurencich Minelli in The Inca World, the human realm had witnessed numerous phases or destruction and recreation in Inca mythology. The Incas saw the gods as striving to create an ever more perfect form of mankind, with cycles of destruction and rebirth dealt upon Kay Pacha: qualities similar to those of our European-influenced present, resembling Plato’s cave’s earthly world of illusions, a realm of the living things striving for freedom, progress, resilient desire, emotions, envy, greed, fear, and chaos on this human order mandated by other humans. Order and stratification visualized in the work of Thomas Kellner’s Visual Analytical Synthesis depart from formal standing architecture and creates a gestalt that houses the original building and metaphorical comments of it. This big contact sheet had an architectural visual morphology that reminds us of rows of buildings in a city block of some imaginary city. These optical illusions are built upon and manipulated by the collective consciousness of well-known buildings embedded with fetishism and celebrated by congregation of peoples, metaphorical commentaries that open up a dialectic conversation and, therefore, an inevitable synthesis. These trembling commentaries function as spring boards which throw the viewer’s imagination into a new visual dimension (synthesis) with loose connections to the original building, but based on it, and they too make the viewer flow through the expansive rhythmical sequence, a drenching of the senses that allows us to get lost in this invented, but orderly, realm. Furthermore, it may resemble representations of the viewers’ brain activity as it dices and digests information. Similar to the emotions brought about by seeing important pieces of architecture for the first time, as monuments, cathedrals, memorials, or comprehending them for the first time: like those which millions of New York visitors experience when they are exposed to the marvelous design and decoration of New York buildings, housing anonymous inhabitants.

Alejandra Delgado’s Fantasmagorias superpose two or more negatives-like images and, while playing with different levels of opacity, blur the full figurative discourse on the buildings’ colorful facades. These multistory and multifunctional Cholets[iii] include the living quarter of the owner’s family and several rental floors for parties and gatherings. These party complexes dedicated to corporate exclusive events are the realm of the flesh, lust, excessive drinking and gluttony, provoking movement of bodies without observance and losing momentarily a balanced life. This behavior provides the opportunity for entities to gain control of themselves. Alejandra’s multi layered imagery hovering between the material and the spiritual allows those ghosts to reveal themselves. These phantoms and ghosts are brought into these contemporary buildings by reenters’ partakers and owners’ unresolved grief and persistent attachment to the dead or violent death[iv].

Hanan Pacha is the upper world, and the realm of Inca gods such as Inti (the sun god) and his sister Mama Quilla (the moon goddess). Incas believed that those who lead a good life would ultimately ascend to Hanan Pacha in the afterlife. Gods and their physical representations connected the upper realm of Hanan Pacha with the lower realm of man. According to Juan M. Ossio in his essay “Contemporary Indigenous Religious Life in Peru”, some sky divinities can be identified as heavenly mediators with earth, such as the planet Venus (the goddess Chasca) and lightning (Illapa).

Others serve as earthly mediators with heaven, such as the Apu mountain spirits that bridged the gap between the realm of man and the heavens of Hanan Pacha. The Inca regarded mountains and their peaks as sacred, at times using them as locations for ritual sacrifices to the gods (sometimes using humans as sacrificial offerings). We imagine our ancestors as residing in the island of the Blessed, the Land of the Dead, the Spirit World, Underworld, Night sky or West, mythic conceptions of sacred places of origin. The transcendent realm, the heavenly world, sacred, is above the earthly world, profane, and worship is the act uniting both. The ambivalent nature of the Holy. On the one hand, life is enriched and renewed through an ever closer relation with the divine; while, on the other hand, the Holy represents the fear of Catholics, Christians, Muslims and Jews, of God’s power as a potentially damaging power, for the forces of the holy that so greatly transcends to humans as a grave danger[v].

Brad’s Rooftops images take us to ambiguous gardens closer to god on the top of buildings, with no visible horizon that liberates us from earthly bodies and separates us from everybody on the highest of the human creation, away from the endless quarrels of Chicago’s streets. These inviting beautiful oases on top of buildings in a concrete towering desert are privets with selective access. They may represent the top layers of society, where just the chosen that has access to them are liberated from chaos, sickness and deaths from the people below these skyscrapers gardens that at times reach too high searching for the false god of profits and empty progress and can be punished by God for vanity.

These projects started as a response and reflection, appropriation and reformulation of buildings as human outcrop. As Gesche Würfel’s co-curator of the project described “Building Dialogs builds dialogs among four artists/photographers concerned with the built environment. We photograph buildings from the top to the basement and examine their architectural structures. The images have been paired to create a dialog between two photos searching for colors, patterns, elements that can be found in the works.” As a consequence, pairing images in a visual dialog creates a new composed individual image. These new original or synthesis that just moments before was the unknown is a symbol of the blend that can be reached in a sincere, open conversation with no personal attacks while avoiding stereotypes.

The unknown is what artists strive for, as Rebecca Solnit describes in her book A Field Guide to Getting Lost: “Certainly for artist of all stripes, the unknown, the idea or the form or the tale that has not yet arrived is what must be found. It is the job of the artist to open doors and invite in prophesies, the unknown, the unfamiliar; it’s where their work comes from, although its arrival signals the beginning of the long process of making it their own”. Also, by blending images, artists are connecting three Pachas, opening passages among three realms that they use to move freely between three Pachas, and in so doing they unveil their role as semi-gods like the Moon and the Lighting according to Inca beliefs, and reinforcing the artist mobility through social classes and their permanence in time confirm our mortal condition.

Fabian Goncalves Borrega

[1]Architect Freddy Mamani was at the forefront of the Cholets emerging on the heights of La Paz, capital of Bolivia.

His design parameters are aligned with Andean Architecture or Neo Andina or Neo Baroque.

[i] Ronnberg, Ami The Book of Symbols, 2010 Taschen Koeln

[ii] Würfel, Gesche, Basement Sanctuaries 2014 Schilts Publishing, Amsterdam

[iii] Caamano Carlos, Fantasmagorias, 2015 Curating, Lima Modern

[iv] Ronnberg, Ami The Book of Symbols, 2010 Taschen Koeln

[v]Ronnberg, Ami The Book of Symbols, 2010 Taschen Koeln

References:

Juan M. Ossio – “Contemporary Indigenous Religious Life in Peru”; Native Religions and Cultures of Central and South America; ed. Lawrence Eugene Sullivan; Continuum International Publishing; 2002.

Laura Laurencich Minelli – The Inca World; University of Oklahoma; 1999.

Garcilaso de la Vega – First Part of the Royal Commentaries of the Yncas; Hakluyt Society; 2010.

Paul Steele – Handbook of Inca Mythology; ABC-CLIO; 2004.

Rebecca Solnit, A Field guide to Getting Lost, 2005 Penguin Books

The Art Museum of the Americas is the oldest museum of Latin American and Caribbean arts in the United States and shows modern and contemporary art, ranging from new figuration to geometric and lyrical abstraction to conceptual art and optical and kinetic art. It offers extraordinary works of art. With over 2,000 works of Latin American and Caribbean origin, it focuses on topics such as cultural exchange, democracy, human rights, security and related development. The AMA is part of the Organization of American States (OAS) and is committed to promoting peace, justice and solidarity among the 35 member states. The Art Museum of the Americas is of great importance for cultural exchange between Latin America, the Caribbean and the United States of America and also serves as a level of political expression. AMA aims to create communities that encompass creative expression, dialogue and learning in which the arts of America address social and political issues and can support an ongoing narrative with the permanent collection of AMA.

Thank you to Fabian Goncalves and Gesche Würfel for including my work in this inspiring post-corona-exhibition.