Ludmila Steckelberg, Brasilia, Brazil / Montreal, Canada

Ludmila Steckelberg is a Brazilian artist, based in Montreal, Canada. She has a Bachelor in Visual Arts and a Master in Museology. She has been working in the series The Absence of all Colors since 2005 and in the series The Album, through 2012 and the present year. She has been making national and international exhibitions and been participating in photography festivals like Kaunas Photo Days in Lithuania. Her work figures in national collections like the one of the Museum of Modern Art from Rio de Janeiro and have been published in books and in magazines. She has been awarded in her home country.

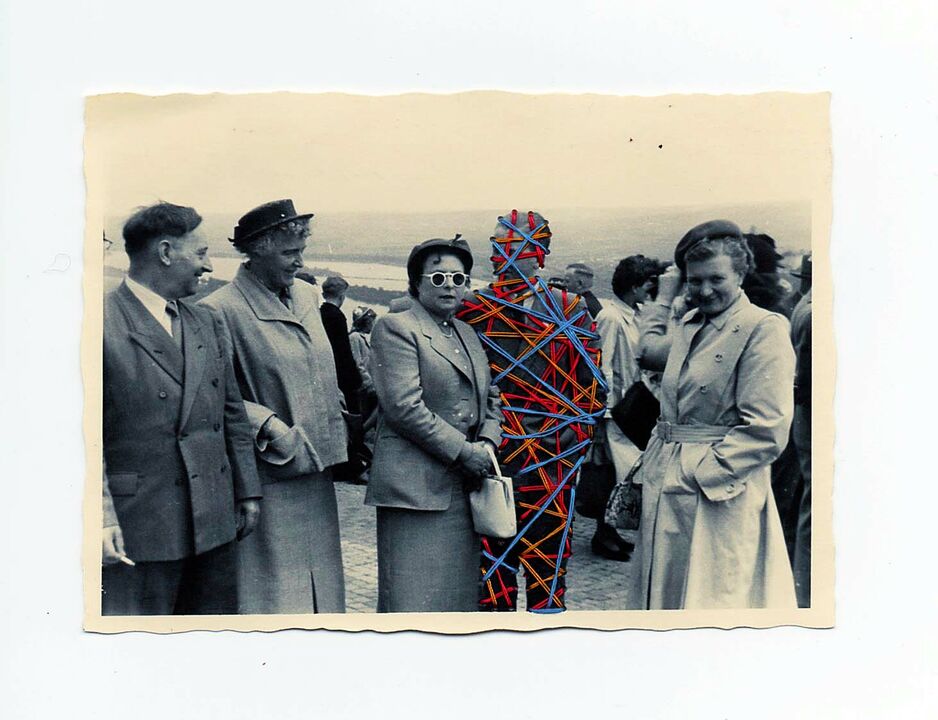

The technique used in this new series, in the contrary of the previous one, has as base real photographs, German ones from the 50’, from which I dissemble the images of people, using needlework. The needlework is a technique that makes part of Brazilian culture for centuries now and is passed from grandmother, to mother and daughter. With this work I am only repeating a natural gesture of perpetuating of tradition.This time, in the perforating action, the contact with the person’s image makes me get in touch with details of them, people that actually, I don’t even know. That creates an intimate connection with the person, transforming the process in an experience extremely intense and emotional.

My work talks about disappearance, emptiness, and how we deal, or not, with it.

The absence of all colors

The technique used in my work, is the scanning of my old family albums, from which I cut the images of the diseased persons, using programs of digital manipulation. The idea is to show images vanishing as the persons in the world, leaving only the emptiness.

In the cut intent, the intimate contact with the person’s image, always a relative, makes me get in touch with details of these people, that sometimes I knew, and sometimes not. That creates a connection – a knowledge – with me and the person, transforming the process in a experience extremely intense and emotional.

The work treats the image of the character, now removed from the photographs – a memory’s instrument – like something that only exists in the memory, without visual or physical reference.

The series speaks about the consuming of images, and how the photography gets others significations when it begins representing something to someone. It talks about death, the emptiness that remains, and how we deal, or not, with it.

Jim Casper

“The conceptual photo-based art work of Ludmila Steckelberg is loaded with meaning. It is pointed squarely at the ideas of memory and loss, time and generations, and our faulty reliance on photography for safeguarding the remembrance of people who were once alive, but are no longer here.

By removing the photographic images of the dead ancestors from her family album, but leaving their crisp silhouettes — dark, empty, ominous ghost-like shadows — Steckelberg has created a powerful visual meditation that moves far beyond the edges of her personal universe.

By “removing” the dead, we are forced to look at one part or the other: the currently living or the forever dead. Clearly, the photographed people and those represented by the silhouettes

were once living contemporaneously. We think of how the survivors have surely changed since the photos were taken. It is difficult to imagine the expressions on the faces of those who have left. Were they as serious or happy at these moments as the faces of the others? Then we wonder about how these people were lost. And when in their lives — shortly after this photo was taken, or decades later? Even though we are not familiar with these particular people, we feel stung by the “injustice” of the baby of the family dying first (the one missing from the high chair) — why the youngest and not the oldest first?

We can think about these things not knowing anything about these people, this extended family. Yet, when a juicy bit of memory knowledge slips out in conversation with the artist (…). This bit of scandalous knowledge ripples through, further animating the rest of the family album photos, and we now peer intently at each to discover some other evidence of quirky behavior. And we wish we could see the face of Uncle Walbron's crazed mother. This makes me realize that Steckelberg is encouraging us to meditate, as well, on the intimacy of a private family photo album (a thing which may no longer survive, itself, in our digital age). We may marvel at the way these photo objects were made "back then", noticing the different formats of the prints with deckled borders, the poses chosen, and the other things that are included within the frames, intentionally or not. Notice the care with which the glued-corners are placed, and the creases in the well-loved photos that have been handled, dreamed upon, remembered with fondness (and sadness, melancholy, nostalgia). Of course, the nature of the family album implies the oral histories that traditionally accompanied these photos stuck into pages — the stories that were told while turning the pages together with a member of the family. Will this tradition disappear as well in our digital age?

This simple idea (cutting out the silhouettes of the dead and removing them from family albums) can be poignant and terrifying, too. A visual record book (a metaphor for personal and collective memory) is being continually diminished. We can imagine a slow sequence of images being removed, death by death, until only the settings remain, and of course, those will have changed or vanished, too, over time.

The violence done to these photographs forces the question: Do we ever expect loss, or does it surprise us with its suddenness and thoroughness? Perhaps we do always anticipate it consciously or not, and perhaps that is why we make photographs. The photo of the mother and baby anticipates a cycle of nurturing, shaping, forming, and then passing on. In this instance, the mother is no longer here, but surely her influence carries on, if only in the private recesses of our own understandings of the players in our lives and their places (full or mysteriously empty) in our own personal galaxies.”

— Jim Casper

Collections

Museum of Modern Art from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Cultural Centre of the Federal University of Goiás, Brazil

Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection

Contemporary Art Gallery of the Federal University of Goiás, Brazil

Antonio Sibasolly Gallery, Brazil

Jatai’s Contemporary Art Museum, Brazil

Links for Ludjimal Steckelberg de Santana

>>> photographers:network selection 2012

>>> photographers:network selection 2008